I recently coached a leader who received feedback that she needed to make more confident, decisive choices. As we began our work together, I asked her to describe how she approached complex business decisions.

I recently coached a leader who received feedback that she needed to make more confident, decisive choices. As we began our work together, I asked her to describe how she approached complex business decisions.

She outlined a thoughtful process: identify the root cause of the problem, gather input from others, consider the impact on stakeholders, weigh the pros and cons, and then decide. With a laugh, she admitted, “It’s not this streamlined though. I tend to get weighed down by the options. I know I’m slow to pull the trigger.”

Curious, I asked about her instincts. When do you pause to listen to yourself?

She replied, “Hmm…I guess I don’t typically do this. I think my instincts surface as I move through the data I’m collecting.”

I invited her to experiment: what if she began by reflecting privately to listen to her instincts and review critical data points before gathering external perspectives? She agreed to try.

Ahead of her annual budget recommendations, she drafted a version of the department budget for her eyes only. Then she followed her usual process of gathering input and considering stakeholder impact. Finally, she returned to her draft, integrating her initial insights with what she had learned from her team.

The result? She felt more grounded and confident in her budget decisions. By starting with her own perspective, she avoided over-indexing on external voices that lacked the full picture. She could compare her instincts with others, identify blind spots, and make adjustments. This balance gave her clarity and alignment with her internal compass while honoring stakeholder input. And while the process took time, she didn’t feel ‘stuck’ in her decision-making process like she often did.

The Broader Lesson

In my years of coaching leaders, I’ve noticed a common tension: many lean too heavily on one end of the spectrum—either their own instincts or external perspectives.

By “instincts,” I don’t mean impulsive reactions, but a reflective, deliberate process of internal sense-making. Nobel Prize–winning economist Daniel Kahneman distinguished between fast, automatic thinking (often prone to bias) and slow, deliberate reflection, which supports better decisions in complex problem-solving.

Leaders who depend only on their internal ‘sense-making’ risk missing critical factors and alienating their teams. In these instances, I see teams struggle to buy-in to a leader’s decisions if their perspectives are never considered.

Conversely, leaders who are heavily invested in collaboration and rely primarily on others’ perspectives may risk overlooking the unique industry, institutional, or relational knowledge that earned them their role. In these situations, I often hear team members express a desire for their leaders to make decisions so that the team can more efficiently move forward.

It’s a fine line that requires nuance. Knowing when to collaborate and share the decision-making process, and when to step in, make the call, and determine the direction for the team, is a hallmark trait of great leadership. Learning the skills to manage decision-making can feel like a process of trial-and-error. It can help to ask yourself a few questions before you begin and as you move through the decision-making process.

- What are my initial thoughts or instincts about this decision?

- What process will I move through to find clarity?

- Who will be impacted by this decision and what input do they need to have in making the decision? (Consider stakeholders, employees, other leaders, etc.)

- How will I balance my instincts with feedback from others?

By intentionally balancing reflective insights with stakeholder perspectives and adapting their approach to the context, leaders can cultivate the agility that brings clarity, confidence, and alignment to even the most complex decisions.

Leo Tolstoy once said, “Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing oneself.”

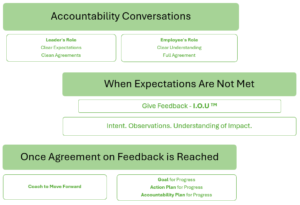

Leo Tolstoy once said, “Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing oneself.” The challenge of addressing employee underperformance requires a clear, targeted approach, one that many executives and mid-level managers aspire to master. However, they can easily miss the mark by neglecting to delineate specific actions within the process. This requires a thorough examination of three pivotal facets of performance improvement discussions, specifically accountability, feedback, and coaching.

The challenge of addressing employee underperformance requires a clear, targeted approach, one that many executives and mid-level managers aspire to master. However, they can easily miss the mark by neglecting to delineate specific actions within the process. This requires a thorough examination of three pivotal facets of performance improvement discussions, specifically accountability, feedback, and coaching.

Clients often tell me that they want to be more strategic with their communication. They share that they find themselves saying more than they’d like and taking too long to get to their point.

Clients often tell me that they want to be more strategic with their communication. They share that they find themselves saying more than they’d like and taking too long to get to their point.